A graph is something that looks like this:

In computer-science lingo, a graph is a set of vertices paired with a set of edges. The vertices are the round things and the edges are the lines between them. Edges connect a vertex to other vertices.

Note: Vertices are sometimes also called "nodes" and edges are also called "links".

For example, a graph can represent a social network. Each person is a vertex, and people who know each other are connected by edges. A somewhat historically inaccurate example:

Graphs come in all kinds of shapes and sizes. The edges can have a weight, where a positive or negative numeric value is assigned to each edge. Consider an example of a graph representing airplane flights. Cities can be vertices, and flights can be edges. Then an edge weight could describe flight time or the price of a ticket.

With this hypothetical airline, flying from San Francisco to Moscow is cheapest by going through New York.

Edges can also be directed. So far the edges you've seen have been undirected, so if Ada knows Charles, then Charles also knows Ada. A directed edge, on the other hand, implies a one-way relationship. A directed edge from vertex X to vertex Y connects X to Y, but not Y to X.

Continuing from the flights example, a directed edge from San Francisco to Juneau in Alaska would indicate that there is a flight from San Francisco to Juneau, but not from Juneau to San Francisco (I suppose that means you're walking back).

The following are also graphs:

On the left is a tree structure, on the right a [linked list](../Linked List/). Both can be considered graphs, but in a simpler form. After all, they have vertices (nodes) and edges (links).

The very first graph I showed you contained cycles, where you can start off at a vertex, follow a path, and come back to the original vertex. A tree is a graph without such cycles.

Another very common type of graph is the directed acyclic graph or DAG:

Like a tree this does not have any cycles in it (no matter where you start, there is no path back to the starting vertex), but unlike a tree the edges are directional and the shape doesn't necessarily form a hierarchy.

Maybe you're shrugging your shoulders and thinking, what's the big deal? Well, it turns out that graphs are an extremely useful data structure.

If you have some programming problem where you can represent some of your data as vertices and some of it as edges between those vertices, then you can draw your problem as a graph and use well-known graph algorithms such as [breadth-first search](../Breadth-First Search/) or [depth-first search](../Depth-First Search) to find a solution.

For example, let's say you have a list of tasks where some tasks have to wait on others before they can begin. You can model this using an acyclic directed graph:

Each vertex represents a task. Here, an edge between two vertices means that the source task must be completed before the destination task can start. So task C cannot start before B and D are finished, and B nor D can start before A is finished.

Now that the problem is expressed using a graph, you can use a depth-first search to perform a [topological sort](../Topological Sort/). This will put the tasks in an optimal order so that you minimize the time spent waiting for tasks to complete. (One possible order here is A, B, D, E, C, F, G, H, I, J, K.)

Whenever you're faced with a tough programming problem, ask yourself, "how can I express this problem using a graph?" Graphs are all about representing relationships between your data. The trick is in how you define "relationship".

If you're a musician you might appreciate this graph:

The vertices are chords from the C major scale. The edges -- the relationships between the chords -- represent how likely one chord is to follow another. This is a directed graph, so the direction of the arrows shows how you can go from one chord to the next. It's also a weighted graph, where the weight of the edges -- portrayed here by line thickness -- shows a strong relationship between two chords. As you can see, a G7-chord is very likely to be followed by a C chord, and much less likely by a Am chord.

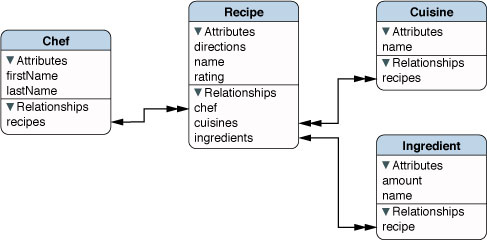

You're probably already using graphs without even knowing it. Your data model is also a graph (from Apple's Core Data documentation):

Another common graph that's used by programmers is the state machine, where edges depict the conditions for transitioning between states. Here is a state machine that models my cat:

Graphs are awesome. Facebook made a fortune from their social graph. If you're going to learn any data structure, it should be the graph and the vast collection of standard graph algorithms.

In theory, a graph is just a bunch of vertex objects and a bunch of edge objects. But how do you describe these in code?

There are two main strategies: adjacency list and adjacency matrix.

Adjacency List. In an adjacency list implementation, each vertex stores a list of edges that originate from that vertex. For example, if vertex A has an edge to vertices B, C, and D, then vertex A would have a list containing 3 edges.

The adjacency list describes outgoing edges. A has an edge to B but B does not have an edge back to A, so A does not appear in B's adjacency list. Finding an edge or weight between two vertices can be expensive because there is no random access to edges–you must traverse the adjacency lists until it is found.

Adjacency Matrix. In an adjacency matrix implementation, a matrix with rows and columns representing vertices stores a weight to indicate if vertices are connected, and by what weight. For example, if there is a directed edge of weight 5.6 from vertex A to vertex B, then the entry with row for vertex A, column for vertex B would have value 5.6:

Adding another vertex to the graph is expensive, because a new matrix structure must be created with enough space to hold the new row/column, and the existing structure must be copied into the new one.

So which one should you use? Most of the time, the adjacency list is the right approach. What follows is a more detailed comparison between the two.

Let V be the number of vertices in the graph, and E the number of edges. Then we have:

| Operation | Adjacency List | Adjacency Matrix |

|---|---|---|

| Storage Space | O(V + E) | O(V^2) |

| Add Vertex | O(1) | O(V^2) |

| Add Edge | O(1) | O(1) |

| Check Adjacency | O(V) | O(1) |

"Checking adjacency" means that we try to determine that a given vertex is an immediate neighbor of another vertex. The time to check adjacency for an adjacency list is O(V), because in the worst case a vertex is connected to every other vertex.

In the case of a sparse graph, where each vertex is connected to only a handful of other vertices, an adjacency list is the best way to store the edges. If the graph is dense, where each vertex is connected to most of the other vertices, then a matrix is preferred.

We'll show you sample implementations of both adjacency list and adjacency matrix.

The adjacency list for each vertex consists of Edge objects:

public struct Edge<T>: Equatable where T: Equatable, T: Hashable {

public let from: Vertex<T>

public let to: Vertex<T>

public let weight: Double?

}This struct describes the "from" and "to" vertices and a weight value. Note that an Edge object is always directed, a one-way connection (shown as arrows in the illustrations above). If you want an undirected connection, you also need to add an Edge object in the opposite direction. Each Edge optionally stores a weight, so they can be used to describe both weighted and unweighted graphs.

The Vertex looks like this:

public struct Vertex<T>: Equatable where T: Equatable, T: Hashable {

public var data: T

public let index: Int

}It stores arbitrary data with a generic type T, which is Hashable to enforce uniqueness, and also Equatable. Vertices themselves are also Equatable.

Note: There are many, many ways to implement graphs. The code given here is just one possible implementation. You probably want to tailor the graph code to each individual problem you're trying to solve. For instance, your edges may not need a

weightproperty, or you may not have the need to distinguish between directed and undirected edges.

Here's an example of a very simple graph:

We can represent it as an adjacency matrix or adjacency list. The classes implementing those concept both inherit a common API from AbstractGraph, so they can be created in an identical fashion, with different optimized data structures behind the scenes.

Let's create some directed, weighted graphs, using each representation, to store the example:

for graph in [AdjacencyMatrixGraph<Int>(), AdjacencyListGraph<Int>()] {

let v1 = graph.createVertex(1)

let v2 = graph.createVertex(2)

let v3 = graph.createVertex(3)

let v4 = graph.createVertex(4)

let v5 = graph.createVertex(5)

graph.addDirectedEdge(v1, to: v2, withWeight: 1.0)

graph.addDirectedEdge(v2, to: v3, withWeight: 1.0)

graph.addDirectedEdge(v3, to: v4, withWeight: 4.5)

graph.addDirectedEdge(v4, to: v1, withWeight: 2.8)

graph.addDirectedEdge(v2, to: v5, withWeight: 3.2)

}As mentioned earlier, to create an undirected edge you need to make two directed edges. If we wanted undirected graphs, we'd call this method instead, which takes care of that work for us:

graph.addUndirectedEdge(v1, to: v2, withWeight: 1.0)

graph.addUndirectedEdge(v2, to: v3, withWeight: 1.0)

graph.addUndirectedEdge(v3, to: v4, withWeight: 4.5)

graph.addUndirectedEdge(v4, to: v1, withWeight: 2.8)

graph.addUndirectedEdge(v2, to: v5, withWeight: 3.2)We could provide nil as the values for the withWeight parameter in either case to make unweighted graphs.

To maintain the adjacency list, there is a class that maps a list of edges to a vertex. The graph simply maintains an array of such objects and modifies them as necessary.

private class EdgeList<T> where T: Equatable, T: Hashable {

var vertex: Vertex<T>

var edges: [Edge<T>]? = nil

init(vertex: Vertex<T>) {

self.vertex = vertex

}

func addEdge(_ edge: Edge<T>) {

edges?.append(edge)

}

}They are implemented as a class as opposed to structs so we can modify them by reference, in place, like when adding an edge to a new vertex, where the source vertex already has an edge list:

open override func createVertex(_ data: T) -> Vertex<T> {

// check if the vertex already exists

let matchingVertices = vertices.filter() { vertex in

return vertex.data == data

}

if matchingVertices.count > 0 {

return matchingVertices.last!

}

// if the vertex doesn't exist, create a new one

let vertex = Vertex(data: data, index: adjacencyList.count)

adjacencyList.append(EdgeList(vertex: vertex))

return vertex

}The adjacency list for the example looks like this:

v1 -> [(v2: 1.0)]

v2 -> [(v3: 1.0), (v5: 3.2)]

v3 -> [(v4: 4.5)]

v4 -> [(v1: 2.8)]

where the general form a -> [(b: w), ...] means an edge exists from a to b with weight w (with possibly more edges connecting a to other vertices as well).

We'll keep track of the adjacency matrix in a two-dimensional [[Double?]] array. An entry of nil indicates no edge, while any other value indicates an edge of the given weight. If adjacencyMatrix[i][j] is not nil, then there is an edge from vertex i to vertex j.

To index into the matrix using vertices, we use the index property in Vertex, which is assigned when creating the vertex through the graph object. When creating a new vertex, the graph must resize the matrix:

open override func createVertex(_ data: T) -> Vertex<T> {

// check if the vertex already exists

let matchingVertices = vertices.filter() { vertex in

return vertex.data == data

}

if matchingVertices.count > 0 {

return matchingVertices.last!

}

// if the vertex doesn't exist, create a new one

let vertex = Vertex(data: data, index: adjacencyMatrix.count)

// Expand each existing row to the right one column.

for i in 0 ..< adjacencyMatrix.count {

adjacencyMatrix[i].append(nil)

}

// Add one new row at the bottom.

let newRow = [Double?](repeating: nil, count: adjacencyMatrix.count + 1)

adjacencyMatrix.append(newRow)

_vertices.append(vertex)

return vertex

}Then the adjacency matrix looks like this:

[[nil, 1.0, nil, nil, nil] v1

[nil, nil, 1.0, nil, 3.2] v2

[nil, nil, nil, 4.5, nil] v3

[2.8, nil, nil, nil, nil] v4

[nil, nil, nil, nil, nil]] v5

v1 v2 v3 v4 v5

This article described what a graph is and how you can implement the basic data structure. But we have many more articles on practical uses for graphs, so check those out too!

Written by Donald Pinckney and Matthijs Hollemans