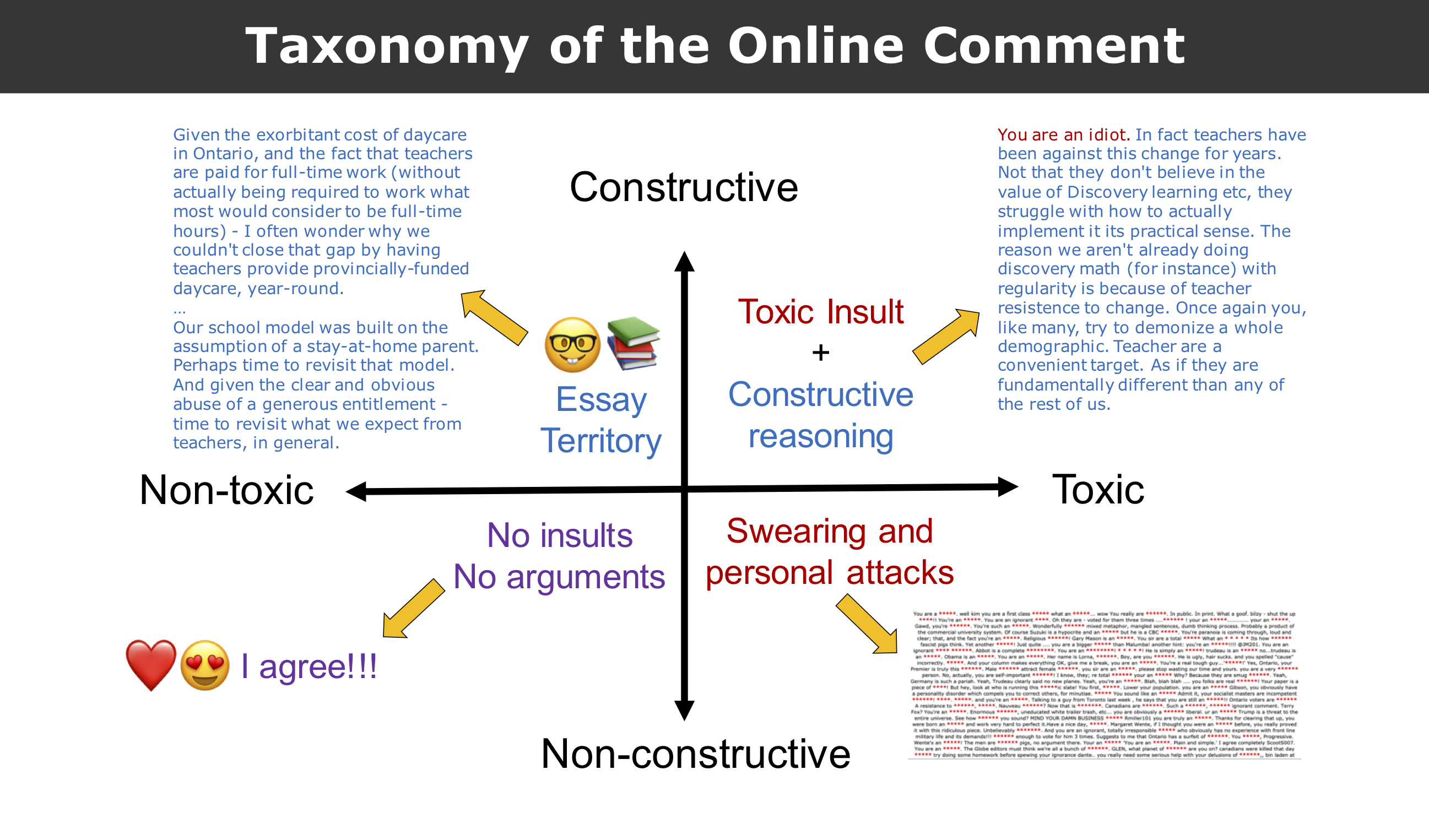

Constructiveness and toxicity are two axes along which we can evaluate a comment. Intuitively, we expect constructive comments to make well-reasoned arguments, while non-constructive comments do not add meaningful discussion. Toxic comments contain insults, profanity or attacks on the authors or people mentioned in an article. Non-toxic comments do not. Any given comment is either constructive and toxic, constructive and non-toxic, non-constructive and toxic, or non-constructive and non-toxic.

A non-constructive and non-toxic comment does not add meaningful discussion but does not insult either. Examples of this type of comment include polite, unjustified agreement or disagreement with the article. In the data we considered, these comments tended to show agreement more often than disagreement.

A non-constructive and toxic comment on the other hand consists of directed malice without providing good reasoning. This type of comment often contains colourful language but this category also includes sarcasm and more subtle insults. Despite the fact that agreement or disagreement with the article's content has nothing to do with a comment being in this category, we found a pattern in the data we considered. Comments in this category tended to disagree with the article's content or show disapproval of the views of the author or others mentioned in the article.

Comments that are constructive and non-toxic read like an essay. They tend to be longer and their sentences are linked cohesively, providing convincing arguments for their point of view. Nobody is insulted, regardless of whether the comment writer agrees or disagrees with the content of the article.

Finally, perhaps the most interesting category is the constructive and toxic comment. Almost paradoxically, they contain well-reasoned arguments as well as hateful language. They sound condescending and often follow a format where they open with a toxic insult and continue with good reasoning. The shift is often so dramatic that if the first sentence was ignored, the comment would land squarely in the constructive and non-toxic category. These comments are more common than one would expect and are particularly intriguing because they do not follow intuition.

Below is a visual depiction of the four categories which also illustrates some examples. The non-constructive and toxic category consists of several examples stitched together where words considered insulting are censored with red asterisks.

With this taxonomy of the online comment in mind, we examine some of the trends in our data, first altogether and then broken up by publication. These graphs all show toxicity on the horizontal axis, the number of comments on the vertical axis, and one line each for constructive and non-constructive comments.

The highest point in the graph at over 200,000 comments is a blue dot, i.e., non-constructive comments. They are low in toxicity - around 0-15% toxicity. Non-constructive and non-toxic comments like "I agree" or "I disagree" fall into this category and make up the majority of online comments in these three publications, as we would expect.

Through most of the graph, non-constructive comments are more common than constructive comments, which also aligns with our intuitions about seeing few logical comments on the internet. However, in the central part of the graph with middling levels of toxicity, constructive comments tend to be slightly more common. Additionally, the peak of the constructive (orange) line is at about 15% toxicity. Both these findings imply that constructive comments tend to contain some small proportion of toxicity. The explanation we suggest for this is that constructive comments tend to provide qualified rather than total agreement or disagreement, unlike non-constructive comments. This qualification gives room for some name-calling in many constructive comments.

The tail end of the graph is towards the right, i.e., high toxicity. This is somewhat unusual because our perception of comments online tends to be that many are nasty and hurtful. But we propose that this impression can be attributed to the negativity bias.

Another point to notice when looking at the leftmost part of the graph is that at a very low level of toxicity, there seem to be may more non-constructive comments than constructive comments - more than twice as many. This means that there are more than twice as many non-toxic comments like "I agree" or "I disagree" than well-reasoned comments without insults.

Now we will consider each publication individually to see how closely their data matches the average case.

The main difference between SOCC comments and the overall pattern is that non-constructive comments are consistently far more frequent than constructive comments at all levels of toxicity.

Additionally, the drop in the number of comments with increasing toxicity is less steep than the overall pattern, indicating that SOCC comments are more toxic on average.

The Tyee has many more constructive comments with the orange line consistently above the blue one starting at about 15% toxicity.

The original pattern at a low level of toxicity of more non-constructive than constructive comments is consistent with the overall pattern.

The Conversation seems to have much fewer toxic comments than the average as the drop in the lines from the left (low toxicity) to right (high toxicity) is very steep.

Most interestingly, the low level toxicity pattern is not seen in this publication, i.e., at 0-15% toxicity, there is a very small difference between the numbers of constructive and non-constructive comments. We attribute this to the nature of the publication. With content from academics and researchers, we imagine that the audience interested in reading these articles is self-selected to be more cautious in their comments.

Topic modelling is a technique to discover the themes (henceforth "topics") discussed in a corpus of documents. Having trained an LDA topic model on the large corpus of SOCC articles, 15 distinct topics were discovered. The top 10 words of each topic is displayed below.

Topic 1 Topic 2 Topic 3

Topic 4 Topic 5 Topic 6

Topic 7 Topic 8 Topic 9

Topic 10 Topic 11 Topic 12

Topic 13 Topic 14 Topic 15

Predictions were first made on the articles. An article was counted towards a topic if the topic model predicted a probability of more than 10% for the topic in that article.

We see clearly that the 3 most popular topics of SOCC articles are topics 14, 10 and 4.

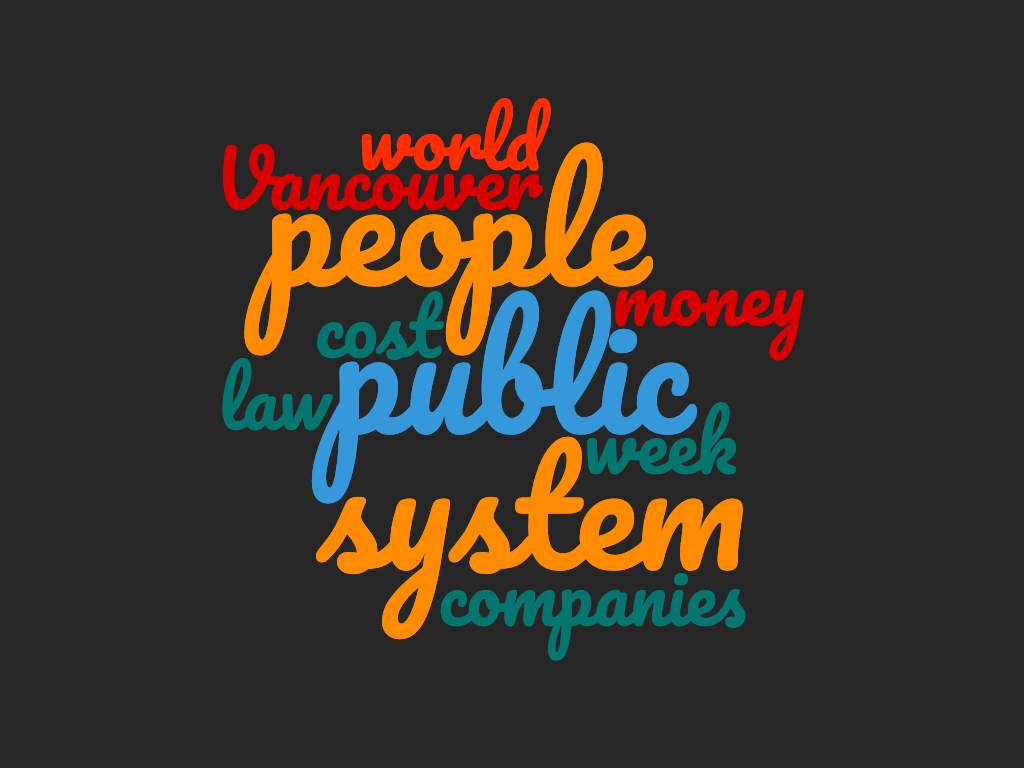

These topics appear political but are not limited to Canada. The most common one, topic 14, contains the words "British" and "Chinese", suggesting international politics and economics. Topic 4 is clearly about Canadian politics at the national level, with the words "government", "NDP", "Liberals", "Harper" and "party". Topic 10 is about "people", "public" and "system[s]", suggesting local news, further emphasized by the appearance of "Vancouver".

When predictions were made on the three comment corpora with the LDA model, similar patterns emerged. The top three topics are the same for both articles and comments and they remain the top three by a big margin. The graph below shows the results for all comments combined, but even when split up by corpus, the results are not far from each other.

These graphs lead us to our first conclusion which is that the proportions of the topics discussed in comments seem to correlate directly with those of articles. This suggests that what people talk about is associated with the articles that they read, as opposed to being disproportionately about other topics.

We cannot conclude from these graphs that people comment more about politics than any other topic, however. This is because if there is a correlation between topics in articles and topics in comments, then they are not independent from each other. To find out what people comment most about, we need to account for and normalize the number of articles in any given topic.

We do this by dividing the number of comments on a certain topic by the number of articles on that same topic. Interesting results emerge, as shown in the graph below.

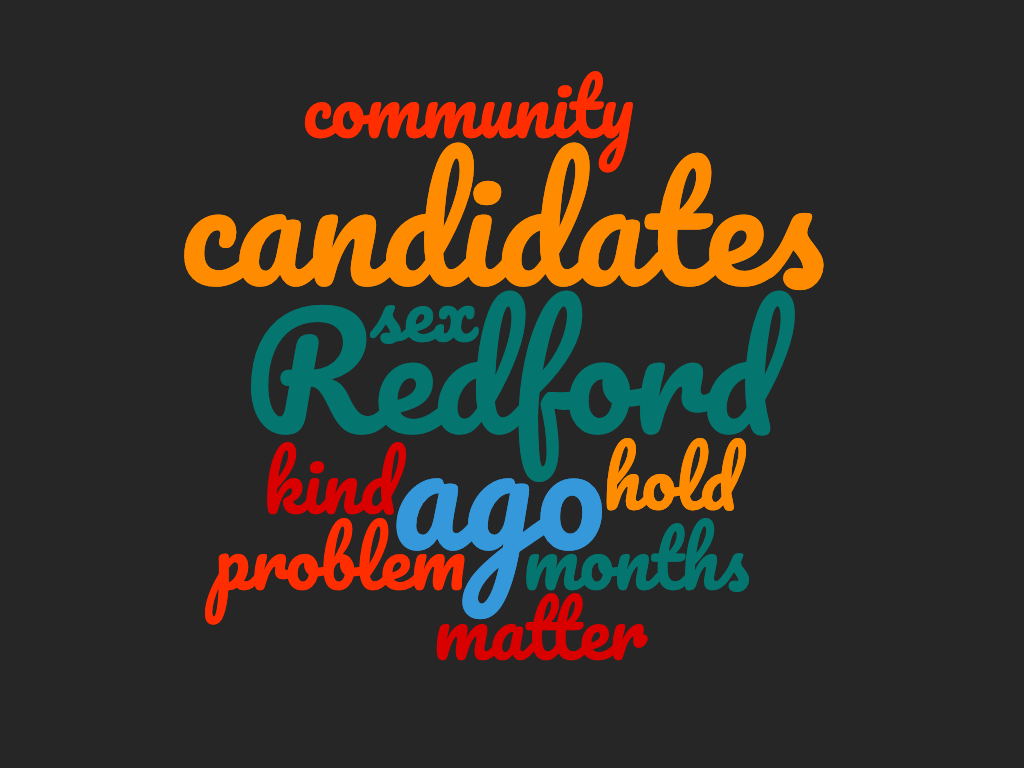

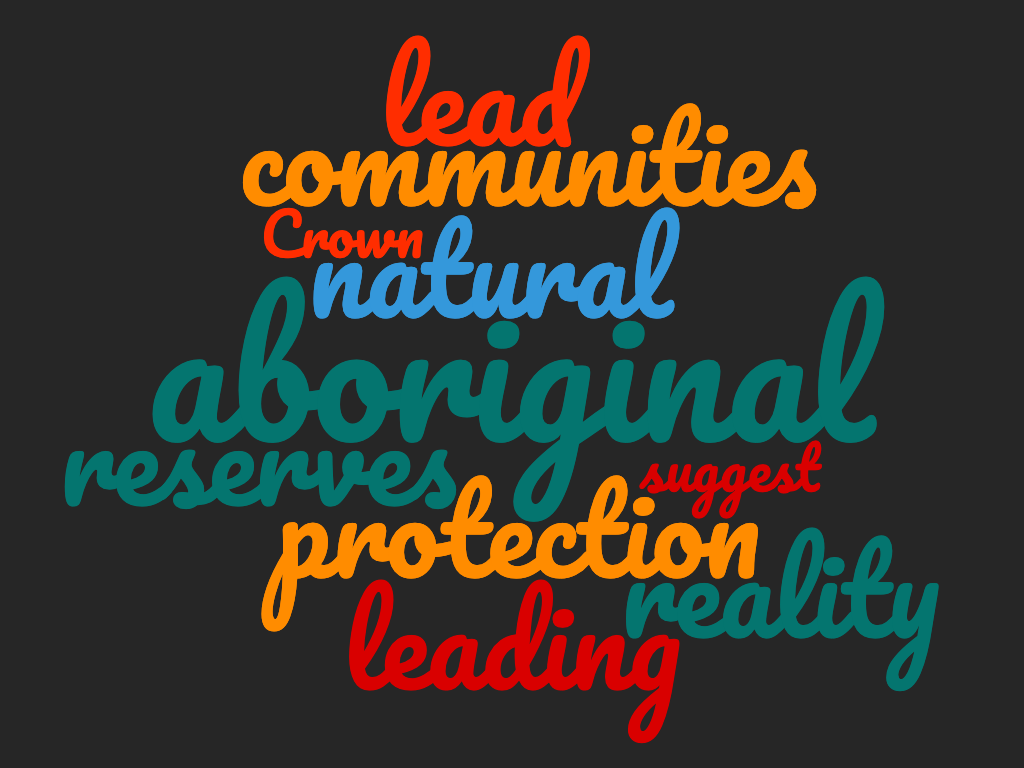

This graphs shows the difference in the proportion of comments about a topic when compared to articles about that same topic. What we see here is a different set of top three topics - topics 6, 7 and 2.

In these topics, we see more people mentioned - "Charest", "Redford" and "Romney". We also see more personal, abstract concepts such as "talk", "problem", "matter", "home", "community", "life" and "death". In contrast to these words, articles tend to be more factual and have more concrete nouns.

At the same time, judging from the words "legislation", "program", "Trade", "Commons", "candidates", "global" and "local", it seems that comments do talk considerably about politics at different levels. This leads to our second conclusion, that people comment more about politics than other topics, but that they bring in personal experience and anecdotes when they do so.

We were interested in combining our results to see if there were differences in the constructiveness of comments by the topics they discussed. It turns out that the answers to this question are quite interesting. We began by counting the proportion of comments by topic that were constructive, over all corpora. Since we are calculating the proportion and not the raw numbers of comments, these results are unaffected by how popular a topic is for discussion. The bar graph below shows the average constructiveness score (a binary-valued prediction) for all 15 topics.

On average, the constructiveness across all topics appears to be between 0.30 and 0.35, indicating that roughly 1 in 3 comments is constructive. The fluctuations in constructiveness bear a striking resemblance to the distribution of articles in each topic, though the changes are less dramatic. As in the number of articles by topic, the top 3 topics are topics 4, 10 and 14. This suggests that there is a higher degree of constructiveness in the comments relating to topics about which more articles are written. Regular discussion in the media of an issue seems to promote better discussions about it.

It is also worth pointing out that there is no clear relationship between constructiveness and the topics most often discussed in comments (topics 2, 6 and 7).

We now look at the patterns within each corpus as there were interesting differences.

SOCC comments are below the average in their constructiveness overall, but the pattern is remarkably consistent with the pattern seen across the board. The only difference is that the separation is larger between topics with less constructive comments and those with more constructive comments.

The overall pattern of constructiveness of comments made on The Tyee's website is consistent with the average case, except that across all topics, the constructiveness comes in higher than the average. Given the large, general audience of this publication, the higher constructiveness could be attributed to better moderation of their comments.

The Conversation has the same pattern as the distribution of all comments put together, with the exaggerated differences as in the SOCC comments.

One point to make is that their average constructiveness is much higher than the other publications, with comments on the top 3 topics (4, 10 and 14) reaching close to a constructiveness value of 0.66. This means 2 in 3 comments on these topics are constructive, twice the average. As before, we would attribute this to the nature of the publication and audience.

We were also interested in seeing if there were differences in the toxicity of comments by the topics they discussed. Our assumption was that certain topics might be more controversial and cause more toxic comments.

To our surprise, this is not the case. Unlike constructiveness, toxicity seems to pattern in roughly the same proportion across topics. The graph below shows the average toxicity score (a decimal prediction between 0.0 and 1.0), over all corpora. As before, we are calculating the proportion and not the raw numbers of comments, so that these results are unaffected by how popular a topic is for discussion.

On average, the toxicity across all topics appears to be about 0.23, meaning that less than 1 in 4 comments is a toxic comment. There is not much fluctuation between topics, a pattern that is maintained across the three corpora. This lack of variation suggests that toxicity in comments is not exacerbated by certain topics over others, but is more likely just a feature of online language. When you click on an article, regardless of what it's about or how often the issue is discussed, there will always be a fixed proportion of comments on it that are toxic.

SOCC comments show a flat, unchanging pattern in their toxicity by topic. They provide support for the claim that there is a fixed proportion of toxic comments on every topic.

The Tyee shows a little more distribution in the toxicity of its comments by topic but these differences are not significant. The average toxicity seems to be at the average of 0.23.

The Conversation has the same overall pattern but just like its better performance on constructiveness, these comments are also slightly less toxic than online comments in general. The average toxicity of comments on The Conversation is around 0.18.

The work in this project barely scratches the surface of the things that could be done with sophisticated topic modelling and systems to quantify constructiveness and toxicity.

The following are potential future directions:

- Constructiveness and toxicity by anonymity of username

- Toxicity by gender / racial background of the author

- Investigation of patterns using more narrow types of toxicity supported by Perspective API such as sexually explicit comments, threats, sarcasm, etc.

- Threading of comments by topic, as a way of quantifying and comparing discussion between readers as opposed to standalone comments

- Toxicity and constructiveness at different stages in a thread as an approximation of Godwin's law

- Relationship between topics in articles to the topics in the comments about them to quantify how much comments stay on topic

- Extending the taxonomy of an online comment to include sentiment (positive or negative feelings towards an article) and examining the relationship between sentiment and the other variables considered in this project